The War That Will End War

Those seeking to justify its purpose often referred to the First World War as, ‘the war to end all wars’. It was a phrase first invoked by H.G. Wells at the outset of the war in 1914. He argued that only the defeat of German militarism could bring about a definitive end to the conflict. The phrase entered common parlance and gave rise to the existential delusion that this monumental sacrifice of human life would ultimately lead to some sort of post-conflict utopia.

After the Armistice there was a Peace Treaty at Versailles, Britain promised to build ‘homes fit for heroes’ and the League of Nations was established in order to minimise the risk of future conflict. The German Empire, Austro-Hungarian Empire, Russian Empire and Ottoman Empire all disappeared and, in their place, newly formed nation states emerged from the ashes of imperialism and yet the rise of challenging ideologies such as communism and fascism meant that peace was never a likely prospect. Less than twenty one years after the Armistice, Europe once again stood on the brink of war. By 1945, tens of millions of people had been killed in a genocidal conflict which concluded with the dropping of nuclear bombs on Nagasaki and Hiroshima. The hopes and dreams of all those who had sought peace so earnestly appeared to lie in ruins.

In truth, it is easy for us to despair at humankind’s inability to live in peace and harmony. The current conflict in Eastern Europe has brought untold misery to millions and, once again, Europe is witness to a conflict that is resulting in death, devastation and the displacement of innocent civilians. At such times, it might be difficult for us to accept that, comparatively, this is one of the most peaceful times in human history.

In 2011, Steven Pinker wrote a book entitled, ‘The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined’. He pointed out that the percentage of people who die violent war-related deaths has declined as societies have become ever more sophisticated and moved away from the hunter-garather model. However, at the time of the book’s publication, Pinker wrote, ‘I know from conversations and survey data that most people refuse to believe this is the case’’. In 2020, the historian Rutger Bregman published a book that offered a relentlessly optimistic view of human nature; one that served to demolish the dismal assessments of those like the seventeenth century philosopher Thomas Hobbes who stated with grim certainty that the life of man was solitary, poor, nasty brutish and short. Bregman argues that our inclination towards kindness and compassion is hardwired into our DNA. Acts of violence and cruelty are the exception and never the norm.

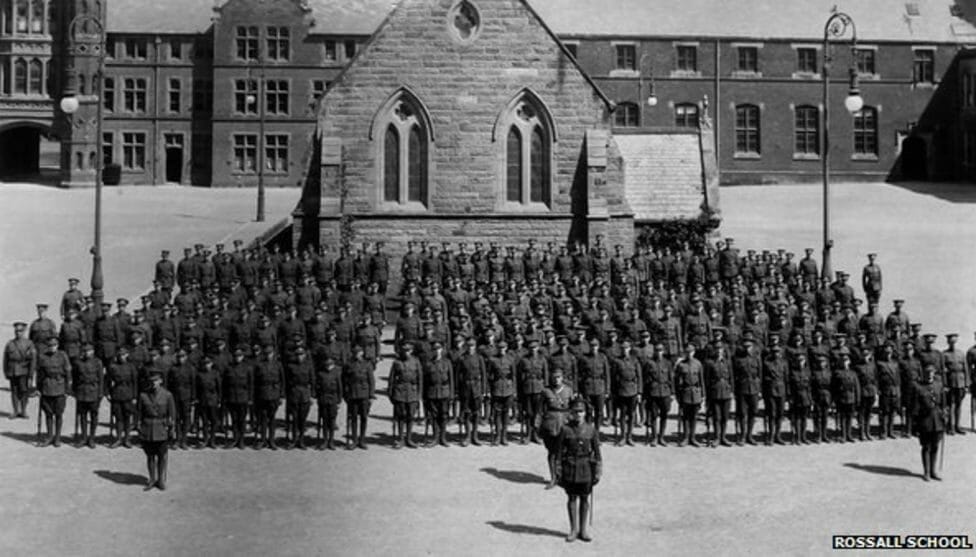

Almost three hundred of the one thousand six hundred Rossallians who served during the course of the First World War were to never return home. Such loss cannot be understood in terms of numbers. As custodians of the collective memory of this School, it is our responsibility to rehumanize a tragic period of history which has gradually slipped away from living memory. When I was your age, it was possible to talk with those who could remember the events that we are reflecting upon today. I even remember attending a royal parade in London where the very last survivors from the British Expeditionary Force were present. The ‘Old Contemptibles’ as they were known had fought in France during the summer of 1914. As an eleven year old, I sensed a tangible connection with the past which has been lost by the passage of time.

During the early part of the twentieth century, it was customary for housemasters to keep journals within which they recorded the academic successes and sporting achievements of their boys. For Rose House, there is just one volume covering the period 1911-27. I should point out that Rose House used to be a boys’ house. This volume is a remarkably personal memorial of loss; it is an affectionate tribute to those who sacrificed their lives. At points the handwriting of the housemaster appears to falter. One can only imagine the grief that he felt when time and again he was called upon to record the names of those missing or killed in action.

In the summer of 1918, just months before the end of the war, we read of George Musgrove Cartmel’s death. He died on 6th April, while flying with the newly formed Royal Air Force. The obituary reads:

Not much is to be chronicled in the case of one whose life has been cut short when but little over nineteen years of age and within a year after leaving school. To all who knew Cartmel, there will remain the memory of a bright sunny disposition, and an unfailing good temper which took the ups and downs of work and play very much as they came, without troubling to ask for reasons and without shirking responsibilities. Starting at the bottom of the school at the age of 14, he worked his way up at first rather slowly but afterwards with spirit when he settled into his stride and a definite goal was before him.

He won his cricket colours as a useful hitter with a good eye and little science but he shone more conspicuously among the forwards in Rugby football, always working his hardest in the scrum.

When the question of his career had to be settled he was irresistibly attracted by the glamour of the Air Service and on leaving school attached himself to the Naval branch.

After the preliminary course at Greenwich he passed on to France and finished his training at a well-known Air School in England.

His nerve and dash marked him out as a promising pilot, and the first engagement in which he is known to have taken part was against a combination of enemy planes so overwhelming that he was lucky to escape with his life.

A brief spell of Hospital followed, and it was in his first flight after his release that he met his end. A schoolfellow in the same squadron observed Cartmel’s machine drop out of the formation. The cause could only be conjectured and he was never seen again alive.

His death was presumed on the discovery of a machine with its two occupants, both unrecognisable, crashed over enemy lines on the same date.

Many of us will remember the absolute joy with which he returned here to spend almost his final leave among us and his boyish delight in the new phase of the old life.

His letters overflowed with affection for his old school, and few sons have we sent out more loyal and devoted than Musgrove Cartmel.

George Cartmel was just one of many Rossalians whose young lives were cut short by war. He is remembered here in the Memorial Chapel and on the war memorial in Kendal. His body was recovered and buried at Millencourt Communal Cemetery in France. It is difficult to know what to make of the inscription on his grave that reads ‘All ye that pass this way tell England that he who lieth here rests content’.

A few months later, the Rose House book records the death of Robert Lightbourn who was from Bermuda. Robert’s death is a reminder that so many of those who lost their lives were fighting for a country that was not even their own. It also reminds us of the enduring nature of Rossall’s international reach. Robert had just entered St John’s College, Oxford but chose to relinquish his place in order to enlist. Shortly after Robert’s death, another boy from Rose, John MacFadyen, died in Northern France. He was the victim of a shell that struck the tank that he was leading over difficult terrain at Cambrai. He had been awarded a History Scholarship at Magdalene College.

It is common to refer to a ‘lost generation’ when reflecting upon the losses of the First World War. Indeed, one morning towards the end of the war, the Senior Mistress of Bournemouth Girls’ High School gathered her Sixth Form girls together and said, ‘I have come to tell you a terrible fact. Only one out of ten of you girls can ever hope to marry’. Of course, this was an exaggeration but the loss of so many men had a profound impact upon the future role of women in society. It is certainly the case that the war seemed to carry off the brightest and best of school communities such as Rossall. Schools with officer training corps suffered catastrophically disproportionate losses because they provided so many young officers who led from the front.

It is sobering for us to reflect upon the shattered dreams of so many young men who left this place to enter the maelstrom of war. Our community bore witness to lives cut hopelessly short, grief-stricken families and the dreadful waste of so much boundless potential. We are proud of the incredible bravery of Rossallians but we mourn the fact that so many lost their lives in conflict.

As we remember those from our own community, we pray for peace. We pray for a time when, as we read in the Book of Isaiah,

They shall beat their swords into ploughshares, and their spears into pruning hooks; nation shall not lift up sword against nation, neither shall they learn war any more.

Jeremy Quartermain

Headmaster of Rossall School